Although Covid-19 is still spreading quickly in many world areas, across Europe, where a progressive re-opening is taking place, the attention is shifting towards the aftermath of the crisis and the possible long-lasting economic damage that it will have caused. There is a distinct possibility that, exactly as the direct demographic impact of Covid-19 has proven uneven, also its consequences on economy and society will be uneven.

The history of plague offers particularly interesting opportunities for reflecting upon the very nature of pandemic shocks. This is because the main plague epidemics are to be counted among the worst mortality crises in recorded history and had a large and relatively easy-to-observe impact. Additionally, they are episodes remote enough that we can observe their longer-term consequences across many centuries. Finally, they constitute probably the best historical examples of the ability of pandemics to have asymmetric consequences.

Two out of the three pandemics in human history characterized by the largest number of victims were caused by plague: Justinian’s Plague of 540-41 AD, which seems to have killed 25-50 million people in Europe and the Mediterranean, and the Black Death of 1347-52, which had up to 50 million victims in those same areas plus unquantified numbers in the Middle East, central Asia, parts of China and possibly elsewhere. Only the Spanish Flu of 1918-19 is considered to have possibly caused more victims than the Black Death: 50 to 100 million worldwide, depending on the estimate. However, in terms of mortality rates, i.e. the percentage of the overall population dying, the Black Death was orders of magnitude worse than the Spanish Flu. In Europe and the Mediterranean, it killed about half the population (the available estimates range from 35 to 60%). Consequently, it is no surprise that the Black Death is usually credited to have had the strongest economic impact.

While the short-term economic consequences of the Black Death were obviously very negative (including the end to much trade and other commercial activity and to many productive activities, let alone the loss of knowledge, skills and competences implied by human losses of such tragic size), most narratives of the long-run economic consequences of that pandemic tend to underline positive effects. These effects include a useful reorganisation of agrarian production towards greater efficiency, a significant increase in real wages, and a re-balancing of population and available resources. Indeed, in Western Europe the Black Death and subsequent plagues seem to have led to the establishment of a new high-mortality and high-income equilibrium which was the premise for quicker economic development across centuries.

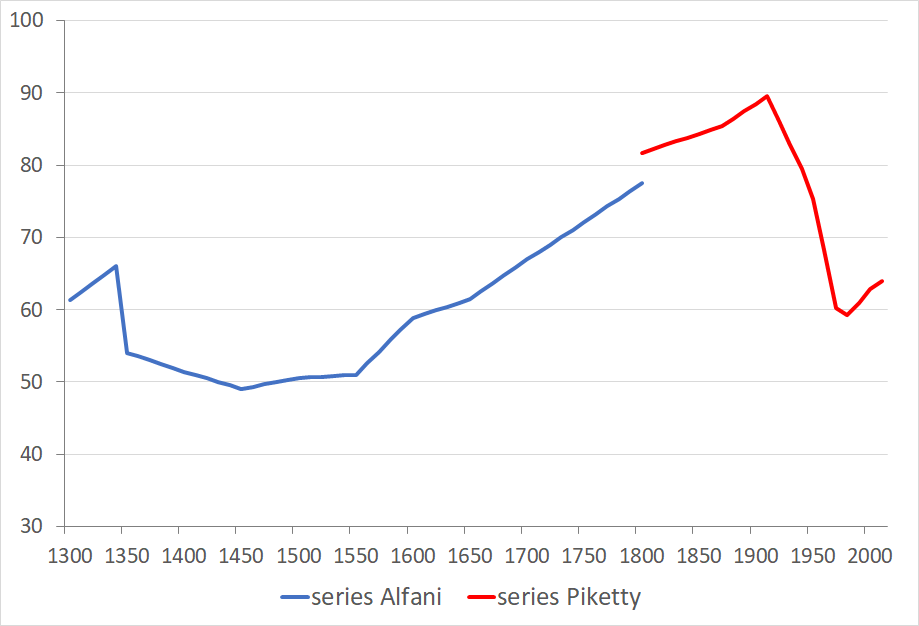

Another positive consequence of the Black Death which has been unearthed by recent research is that it caused a significant reduction in economic inequality, at least in virtually all cases when have reliable information about the immediate pre- and post-pandemic conditions (which mostly refers to a range of Italian states). This can be seen, for wealth inequality, in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. The share of wealth of the richest 10% in Europe, 1300-2010

Source: https://voxeu.org/article/europe-s-rich-1300

During the more than seven centuries covered by the figure, the Black Death triggered one of just two phases of systematic inequality decline (the other being connected to the two World Wars and the difficult interwar period). In the aftermath of the plague, the richest 10% of the population lost their grip on between 15% and 20% of overall wealth. This decline in inequality was long-lasting, as the richest 10% did not reach again the pre-Black Death level of control on overall wealth before the second half of the seventeenth century. The reduction in inequality had two main causes. First, the aforementioned increase in real wages of skilled and unskilled workers and the generally more favourable conditions experienced by labourers. Second, the fragmentation of large patrimonies caused by extremely high mortality in the context of the partible inheritance system, which in the late Middle Ages characterized many European areas, like Italy. This resulted in many people inheriting more properties than they needed or wanted. Consequently, it led to an unusual abundance of property being offered on the market. Together with higher real wages due to the scarcity of labour, this situation helped a larger part of the population gain access to property.

It would be improper, however, to draw from inequality reduction after the Black Death lessons of immediate applicability to the Covid-19 crisis. Particular conditions prevailed. Firstly, the extremely high mortality rates which made labour relatively scarce. Secondly the rules governing the inheritance systems. Fortunately, Covid-19, due to its epidemiological characteristics, will not cause a large-scale contraction of the labour force – but for the same reason, it is also to be expected that it will not cause any reduction in inequality. On the contrary, by leading to exceptionally high unemployment, especially among the poorest and most economically fragile groups, Covid-19 will almost certainly cause a significant increase in economic disparities. Another reason for caution is that not even all large-scale plagues have reduced inequality. The case for which we have the best information is that of the seventeenth century plagues that affected in a particularly severe way Southern Europe. In Italy, they led to the loss of between 30 and 40 percent of the population: fairly close to the 50% or so of the Black Death. But on this occasion, inequality reduction was extremely limited – almost to the point of being undetectable based on the available historical documentation. This is probably because of the very different institutional framework: in the centuries following the Black Death, when it had become clear that plague was to remain a recurrent scourge, the richest families started to protect their patrimonies from unwanted fragmentation by using institutions, like the fideicommissum (entail), which allowed testators to derogate from the general rule of partible inheritance.

The diverse long-term outcomes, in terms of inequality, after the Black Death of 1348 and the 1630 plague are indicative of the fact that not even pandemics caused by the same pathogen and having similar epidemiological characteristics (including in terms of mortality rates), necessarily have the same economic effects. This is even more clear if we look at the ability of large-scale plagues to cause economic divergence between regions and worlds area in the long run.

The fourteenth-century Black Death is usually considered the best example of a pandemic having positive economic consequences in the long run. This general story, however, is not true for each and every affected area. Some scholars have argued that the pandemic might lie at the root of the Great Divergence between Western Europe and East Asia, although more research on Asia is needed to confirm this, which remains a highly speculative hypothesis. But even within Europe and the Mediterranean area, which were affected in a broadly similar way by the Black Death and for which we have relatively abundant data, the economic shock caused by the pandemic proved asymmetric because of the differing initial conditions. In fact, in areas that were relatively under-populated to begin with, like Ireland or Spain, the Black Death set economies on a lower, not a higher path of development. In Spain, in particular, the pandemic destroyed the equilibrium between scarce population and abundant resources upon which a quite prosperous kind of trade-oriented “frontier economy” had been built. As a consequence, it interrupted a phase of quick growth that had been ongoing for 70-80 years, and the pre-plague levels in per-capita income were not recovered before the late 16th century, and then only temporarily. In Eastern Europe, it is possible that the Black Death contributed to foster the so-called ‘second serfdom’, with negative economic consequences in the long run. Finally, in the Mediterranean, the Black Death proved very damaging to Egypt. There, high population density was required to maintain a very complex irrigation system. After the pandemic had destroyed 40% of the Egyptian population, adequate maintenance of the hydraulic system proved impossible to ensure, and the irrigation capacity started to deteriorate. The hydraulic system finally collapsed and remained for centuries in precarious conditions, which entailed a huge and permanent drop in both absolute and per-capita agrarian output. Note that Egypt and Spain suffered because of the Black Death for entirely different reasons, and probably not because of higher than average mortality rates – on the contrary, both regions seen to have experienced lower than average pandemic mortality (certainly in the case of Spain, while for Egypt the evidence is somewhat more uncertain).

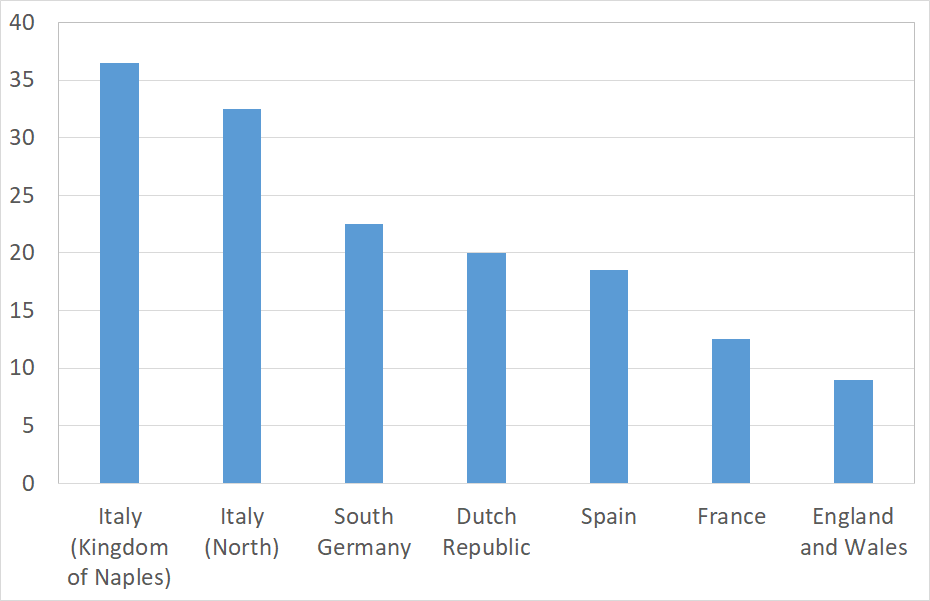

The asymmetric and divergence-inducing character of the economic consequences of large-scale, lethal pandemics is further confirmed when looking at the seventeenth century, when Europe was affected by the worst plague epidemics since Justinians’s Plague and the Black Death. In this instance, and in obvious contrast with the case of the Black Death, the asymmetry resulted primarily from large differences in human losses across the affected areas. If we add up the victims caused by different plague waves during the seventeenth century and compare them to the estimated population ca. 1600, we discover that in south Italy (Kingdom of Naples) they were in the range of 30 to 43%, and 30 to 35% in north Italy. At the other extreme, seventeenth-century plague intensity in England and Wales was in the order of 8-10% of the population existing at 1600, as can be seen in Figure 2. Additionally, in north Europe these losses were the accumulated result of a series of plagues (for example, Amsterdam was affected by six distinct episodes during the seventeenth century, and London by four), while in the case of Italy, no community we know of was affected by more than one (relatively massive) plague event during the century. So, for Italy, the reported results can be understood as the mortality rates for the plague of 1629-30 in the North (about two million victims) and for that of 1656-57 in the South (870,000 – 1,250,000 victims).

Figure 2. Plague intensity in Western Europe during the seventeenth century (cumulated number of victims throughout the century over population at 1600, %).

Sources: elaboration from data in Alfani 2013. The figure reports mid-points in ranges of estimates.

Italy had been the forerunner in the development of effective systems to combat the plague, starting soon after the Black Death, but in the seventeenth century was affected more severely than other European areas, notwithstanding its exceptionally developed institutions and practices to fight the plague. At that time, in Italy, anti-plague interventions included surveillance and quarantine facilities at both estuarine and maritime ports, at mountain passes, and at political boundaries. Within each state, infected communities or regions were isolated. Within each infected community, human contact was limited by quarantines and other temporary restrictions on the freedom of movement. These and other instruments that were developed to fight the plague remain today crucial components of our strategy to contain pandemics, including Covid-19. But, today as in the past, even the best anti-pandemic policies do not always prove successful. For example, in 1629-30 plague entered north Italy with infected armies coming from France and Germany to fight in the War of the Mantuan Succession – and nobody has ever been able to impose a quarantine on an enemy army. This being said, the exceptional severity of plague in seventeenth-century Italy remains an epidemiological puzzle, especially if one considers that without the containment measures that the Italian states attempted to apply, mortality might have been even worse.

These exceptionally severe plagues affected Italy (and other parts of south Europe) at the worst possible moment in economic terms. In the early seventeenth century, the Italian economies were facing very intense economic competition from north Europe, partly due to the opening of the Atlantic trade routes. In this context, which was also one of rampant mercantilist protectionism by competing economies, such damage to the productivity of the labour force and the sharp contraction in domestic demand due to large population losses prevented a quick recovery. Consequently, the contraction in total produce levels and in the fiscal capacity of each Italian state proved permanent. In other words, the seventeenth-century plagues had helped shift some of the formerly most-advanced European economies to a lower development path, contributing to the so-called Little Divergence between Northern and Southern Europe. To confirm the view that the medium and long run consequences of the 1630 plague were overall negative for North Italy, we find no trace, after the epidemic, of an increase in real wages there. Indeed, if we look at a range of series of real wages of masons in northern Italian cities, the only place where some increase after 1630 can be detected is Genoa – which was also the only major city of North Italy spared by plague in that year. Interestingly, Genoa would be the only major city in the North struck by the subsequent plague in 1656-57. Apart from areas in Liguria, this later epidemic affected exclusively the South and the centre of Italy. In the city of Rome there followed a decline, not an increase in real wages of both skilled and unskilled workers after the plague. Another possible positive consequence of pandemics, which was not seen following the seventeenth-century plagues in Italy was inequality reduction, as has been discussed in the earlier section.

But even if we further focus our analysis, to consider only the effects within similar areas of Italy, the shock caused by the seventeenth-century plagues remains asymmetric. This is certainly the case for Italy at the time of the 1629-30 outbreak. Firstly, this epidemic affected the urban economy more severely than the rural (in cities, many skilled workers died and could not be replaced quickly). Secondly, plague severity was not the same across regions. Mortality was exceptionally high in the Republic of Venice in the northeast of Italy and relatively mild in the Duchy of Savoy in the northwest, possibly thanks in part to its mountainous and upland terrain, which allowed for a somewhat more efficient containment of the epidemic.

The different demographic impact of the seventeenth-century plagues could well have led to within-Italy subsequent economic divergence, adding a further layer to the overall picture of how such epidemics may have caused divergence on a continental scale. In particular, the plague may well have proved fatal for the economic fortunes of the Republic of Venice, which for centuries had been the real centre of the European and Mediterranean economy. According to recent studies, the 1630 plague, which was exceptionally severe in this part of Italy killing about 40% of the overall population, worked in combination with the terribly costly War of Candia (1645-69) to displace the unfortunate Republic towards a lower growth path.

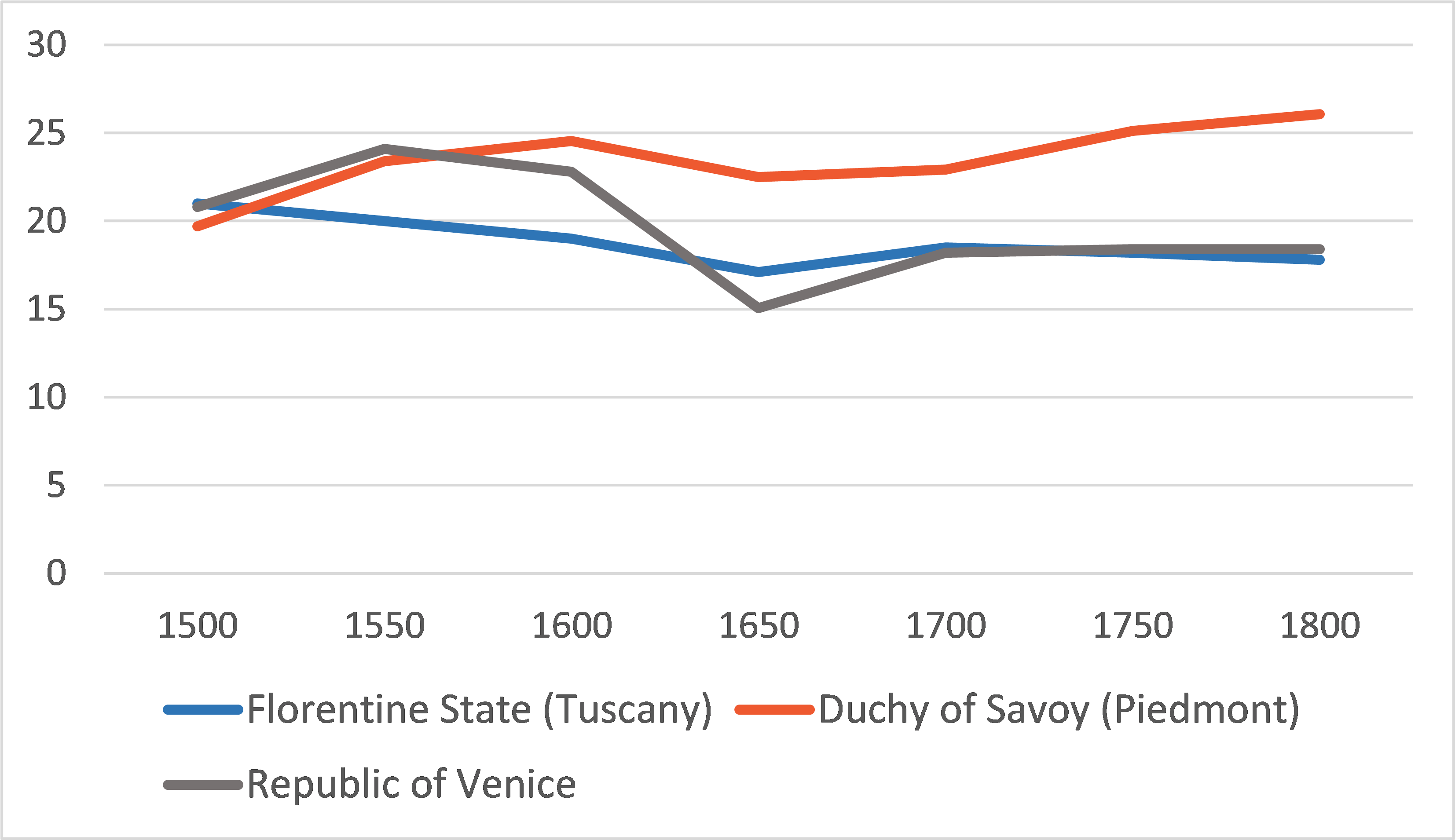

While circumstances led the Republic of Venice to suffer more than others because of the 1630 plague, the only Italian state that might have been able to profit from the situation was the Duchy of Savoy. A crucial factor seems to have been that this part of Italy was relatively spared by the epidemic, hence here demographic and economic recovery proceeded at a quicker pace. Indeed, by the eighteenth century, the Duchy of Savoy had become the most economically dynamic of the Italian states, as well as the most militarily powerful. Figure 3 shows the divergent economic trajectories followed by some Italian states using urbanization rates as an indicator of overall economic development. Note that plague alone could not have led to this outcome, but probably it provided a strong stimulus towards it, and created the ideal conditions for the rise of the Northwest, which in time would become the cradle of Italian industrialization. If seen from this perspective, then, for the Northeast (the Republic of Venice) the plague was the origin of a double process of decline: in comparison to its traditional competitors in North Europe (the Low Countries, to begin with), but also to other Italian states.

Figure 3. Urbanization rates in some Italian pre-unification states, 1500-1800 (cities > 5,000)

Source: elaboration from data in Alfani and Percoco 2019.

The history of plagues confirms the ability of large-scale pandemics to have deep and long-lasting economic consequences. Sometimes these consequences were overall positive. The best example, somewhat surprisingly given its deserved reputation for epochal tragedy in the short-term, is the Black Death in western Europe. However, in many other instances, which could easily amount to the majority of cases, the economic effects of severe pandemics were negative. Indeed, as the fourteenth-century Black Death and its aftermath has attracted much greater scholarly attention than other episodes, there is a risk of drawing general conclusions from what was, in many respects, an exception. An additional reason to be cautious when trying to infer from the history of plague lessons useful for the Covid-19 era, is that the consequences (both the positive, and the negative) of pandemics of this kind were strictly related to very high mortality rates. The Black Death made labour scarce and favoured the (surviving) workers, but this does not tell us anything of use when trying to figure out the possible consequences of Covid-19, which on the contrary is expected to increase unemployment rates and to make the relative conditions of labourers weaker.

This being said, history does tell us something useful for the current crisis. A crucial point is that it confirms that severe pandemics can produce asymmetric shocks because of differences in the initial conditions in different states and regions and this can often be independent of the variation in the local mortality rates. Indeed, the history of plague also clarifies the “unjust” character of asymmetric shocks of this kind, as their local economic consequences depend upon unpredictable epidemiological factors and not only upon the quality of the health institutions and of the policies for pandemic containment. In the seventeenth century, Italian health institutions and anti-plague policies were probably the most advanced and effective in Europe. Yet, when the infection was brought into the Peninsula by enemy armies, its population suffered an epidemic much worse than anything seen in North Europe in early modern times.

It is also important to note that in the political-institutional context of medieval and early modern Europe, rivalry and open hostility among states seems to have amplified the capacity of pandemics to damage some to the advantage of others. Even the Black Death resulted in both winners and losers. So, in today’s situation, when we remain in the dark about the final severity that the Covid-19 pandemic will have in each single region or state and about its impact on national economies, collective answers to the crisis, which in continental Europe for instance, would require co-ordination by the EU, and solidarity both within states and at the international level seem to be the most rational choice for risk-averse governments and indeed, they are highly advisable.

Alfani, G. (2013) ‘Plague in Seventeenth Century Europe and the Decline of Italy: An Epidemiological Hypothesis’, European Review of Economic History 17, 3, pp. 408–430.

Alfani, G. and Murphy, T. (2017) ‘Plague and Lethal Epidemics in the Pre-Industrial World’, Journal of Economic History 77, 1, pp. 314–343.

Alfani, G. and Percoco, M. (2019) ‘Plague and Long-Term Development: the Lasting Effects of the 1629-30 Epidemic on the Italian Cities’, Economic History Review 72, 4, pp. 1175–1201.

Álvarez-Nogal, C., Prados de la Escosura, L. and Santiago-Caballero, C. (2020) Economic Effects of the Black Death: Spain in European Perspective, Instituto Figuerola Working Papers in Economic History 2020-06.

Borsch, S. (2015) ‘Plague, Depopulation and Irrigation Decay in Medieval Egypt’, in Green, M.H. (ed.), Pandemic Disease in the Medieval World. Rethinking the Black Death Kalamazoo and Bradford, pp. 125-156.

Broadberry, S. (2013) Accounting for the Great Divergence, LSE Economic History Working Papers No. 184.

Clark, G. (2007) A Farewell to Alms: A Brief Economic History of the World, Princeton.

Herlihy, D. (1997) The Black Death and the Transformation of the West, Cambridge MA.

Pamuk, Ş. (2007) ‘The Black Death and the origins of the ‘Great Divergence’ across Europe, 1300–1600’, European Review of Economic History 11, pp. 289–317.

Voitgländer, N. and Voth, H.-J. (2013) ‘The Three Horsemen of Riches: Plague, War, and Urbanization in Early Modern Europe’, Review of Economic Studies 80, 2, pp. 774–811.

Download and read with you anywhere!

Sign up to receive announcements on events, the latest research and more!

We will never send spam and you can unsubscribe any time.

H&P is based at the Institute of Historical Research, Senate House, University of London.

We are the only project in the UK providing access to an international network of more than 500 historians with a broad range of expertise. H&P offers a range of resources for historians, policy makers and journalists.